The North Dallas home of Michael Serrecchia and his husband Michael Robinson is tastefully festooned with countless memorabilia from his Broadway career, from his pass to the 1976 Tony Awards to gold records and the gold silk top hat that is instantly identifiable as part of ‘A Chorus Line’ history. (Photography by Arnold Wayne Jones)

Upon the 45th anniversary of ‘A Chorus Line,’ original B’way cast member Michael Serrecchia reflects on the impact of that one singular sensation on the arts, culture and himself

ARNOLD WAYNE JONES | Executive Editor

jones@dallasvoice.com

A little more than five years ago, when live theater was still very much a thing, Michael Serrecchia flew to New York with his husband Michael Robinson to see a preview performance of a new musical that was destined to open soon on Broadway. It was April 16, 2015, and after listening to a brief medley, Serrecchia was invited onstage at the Public Theater to take a bow.

It wasn’t a new experience for him — in fact, it was an amazing bit of deja-vu. Because exactly 40 years earlier, on April 16, 1975, upon that very stage, it was not that new show — called Hamilton — that was performed, but the Off-Broadway opening night of A Chorus Line. And the American musical theater hasn’t been the same since. Indeed, in many concrete ways, Hamilton wouldn’t — couldn’t — exist if A Chorus Line hadn’t paved the way.

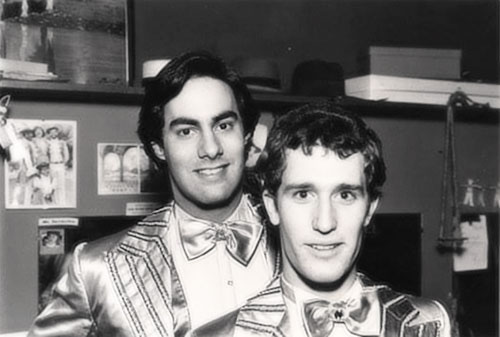

Serrecchia with a fellow cast member during the run original run of ‘ACL.’

This week (July 25, to be exact) marks the 45th anniversary of the day that ACL moved from the Public to the Shubert Theatre on 44th Street, making the transition from Off- to Broadway proper and into … well, not just history, but legend.

“Someone from England [contacted me recently] and said, ‘You know that you’re one infinitesimal part of a group that achieved international impact, right? This doesn’t happen to people,’” Serrecchia recalls. Oh, he knows.

There was a time when musical theater was as much a part of the fabric of society as the internet is today. “Broadway was where Americans got their music,” Serrecchia, who teaches theater in Dallas now, explains. “Before the integrated book musical [was introduced by Oklahoma in 1943], the composers would all write songs for the show — songs! Intended to be sung, not part of the plot. Music drove the cart; after Oklahoma, story drove the cart. That led to the big change in the hierarchy of the musical director being king to the stage director being king.”

Up until the British Invasion, it was always the Broadways shows that drove the music on the radio. After the rise of rock, that changed; it wasn’t until Louis Armstrong had a surprise hit with the single to “Hello Dolly” that Broadway put the Beatles and Elvis on their ears. That wouldn’t last, though. Aside from one-off hits like “Memory” or “All That Jazz,” the era of Broadway shaping popular music tastes has ended.

(In a strange irony, nowadays many Broadway musicals are jukeboxes, pulling their songs from preexisting catalogues of pop songs from the likes of ABBA (Mamma Mia), The Four Seasons (Jersey Boys) and the Brill Building (Beautiful).)

But in the early 1970s, there were still enough folks around who were there during the glory days of Broadway that they were anxious to forge a new path — to innovate and rediscover what theater could still accomplish. And one of those was a man named Michael Bennett.

The invention of a new art form

It might be enough to simply be a member of an ensemble who once appeared in a beloved play. But for Serrecchia and many other principals from that original production, A Chorus Line represents so much more. You could argue it was the original “verbatim play,” the trend of quasi-documentary modern theater based on interviews with actual participants (think The Laramie Project and a host of others). Because in the early 1970s, Serrecchia was one of a handful of dancers — “gypsies” they called themselves — who participated in the soul-baring interviews that formed the basis for ACL script, and forever transformed the face of musicals. Anecdotes he told at a series of sessions circa 1974 became the basis for lyrics and dialogue for a range of characters and entered the theater lexicon.

It all began at a bitch session at Barrymore’s, a storied restaurant on 45th Street (long since torn down), between Tony Stevens and Michon Peacock, a generation of gypsies ahead of Serrecchia. (He wasn’t at the meeting, but the story is well-documented.)

“They were there after a show, smoking and drinking and eating those goddamn cheeseburgers, bitching up a storm, mostly about Mitzi Gaynor,” Serrecchia says. “They were high on booze and cigarettes, and started saying ‘Why doesn’t anyone write a show about us? We make all those incompetent stars look good!’”

Serrecchia with actor Jonathan Groff, one of his biggest fanboys.

They took the idea to Michael Bennett, a fellow gypsy who had met with some success already as a choreographer for shows like Promises, Promises and Follies. Bennett invited a bunch of dancers to his studio between Chelsea and 14th Street, and after a class, “he put the tape recorder in the middle of the floor with some bottles of cheap wine,” Serrecchia says. “He said, ‘I have no idea what this is or where it is going. I just want you to tell me why you started dancing.’ He was very smart in the way he did this — he went first, telling us things we didn’t know about him: intimate, personal, vulnerable.” The gypsies followed suit.

A few months later, many of those in the sessions, including Serrecchia, returned for more interviews, this time at Bennett’s apartment … and with a team of creatives in tow: playwright James Kirkwood, composer Marvin Hamlisch, lyricist Ed Kleban. The group had, in essence, invented the theater workshop: A process whereby a crew gathers to collaborate over time to create a new work from scratch, not day players hired to fill in the gaps. They spend months honing it. “I honestly can’t remember if we were paid $50 a week or $100 a week — you try living on that in New York City, even in the 1970s!” Serrecchia recalls.

Not that there was much else going on. Broadway — New York City itself — was in a massive slump. During the Golden Age of Broadway in the years around the end of World War II, dozens of musicals would open in a single season; by the early 1970s, maybe half a dozen would open along dilapidated streets where few locals or tourists would venture.

“It was so hard to get a job then,” Serrecchia says. “It was derelict. We had Ed Koch walking down the streets shouting out, ‘How’m I doin?’ while dodging bricks.” Having a hand in inventing a new musical (and after all, Hamlisch had just won three Oscars so had some real cred) beat waiting tables.

Even this new methodology was brutal. The original group of storytellers was whittled down to 24, with people actually having to audition to play characters based in part on themselves. (Serrecchia did get to play his “I can’t keep my head up when I dance” self.) Another of the original members, Nicholas Dante, had told a story of such power that his recollection was placed, almost verbatim, into the show as Paul’s monologue, and he was given a co-authorship credit. After several months, the book was taking shape. But there was still a long way to go.

The next step, following Bennett taking the idea to producer Joseph Papp — “Uncle Joe” as he was belovedly called — was to have what are called “backers auditions.” That’s when some monied theatrical angels come to a rough-draft performance to test their interest in writing checks to get the show off the ground. Papp had only recently founded the Public Theater, and its commitment to new and classic works wasn’t exactly a cash cow; the show needed dollars. And that first performance was a disaster.

“All we had was one song that didn’t make it into the show, and then a series of 17 monologues with a couple of dance numbers in between. It ran four and a half hours; it was unbearably awful,” Serrecchia recounts.

How awful? Three of the actors quit that night, including one who would have played the leading role of Zach. His name? Barry Bostwick. But Bennett was not dissuaded; he actually walked away with a fistful of seed money that night.

“It wasn’t a show, it was a workshop,” and people understood that. Plus, “Michael [Bennett] could sell ice to an eskimo,” Serrecchia recounts. And he knew he could make the show work. “Michael’s true genius was his ability to edit and surround himself with the best of the best creatively.”

To fit all the stories into a two-hour, intermission-less run time, “the montage was born,” the series of solos that begins with “Hello Twelve, Hello Thirteen, Hello Love.” “Everyone who had an adolescent issue were whomped into the montage,” he says. That includes the three women who work out their traumas during dance class called “At the Ballet.”

A dream realized

Finally, opening night of the original Off-Broadway run at the Public was upon them. But Serrecchia recalls the experience as one of surprising calm.

“We were so invested in it emotionally — it was more than a show; it was our lives. When we were all together Off-Broadway there was no derision — everybody toed the exact same line. It was the most beautiful spirit of unison playing, the most ethereal, wonderful expression of camaraderie. I don’t think we were scared. We weren’t doing a show we were talking about ourselves, and it was honest and true and straightforward, and we couldn’t wait for people to see it. And they liked it! That was all we cared about. But when we found out how much they liked it…? It was crazy, man.”

Literally from the day after the first preview performance, a seat to A Chorus Line was the hottest ticket in town. You think there was madness over Hamilton? Imagine that ten-fold.

“No one was expecting the sort of reaction, but after the first preview, the theater was sold out every night. Not just sold out: Everybody and their mother wanted tickets,” Serrecchia says. They were unprepared for the impact. The first Playbill was just a mimeographed few pages held together by a staple; Serrecchia still has a copy. And the explosion continued.

“It wasn’t just Broadway — it resuscitated New York City economically. A Chorus Line made such an impact the Shubert Theater became a destination for New Yorkers and international tourists.”

Transformation and legacy

By the late ’60s came the first inkling of “the triple threat:” Performers who could sing and dance and act. That became solidified with ACL. “The workshop concept meant you weren’t hiring a singing chorus and a dancing chorus and a principal cast — those are three different casts. You had to do it all or there was no room for you on Broadway anymore,” Serrecchia says. It made Broadway more affordable: No more lengthy out of town tryouts. You didn’t have $10 million in advance, “just a benefactor with a barn — we were back to Judy and Mickey!”

Serrecchia stayed with the show for four-and-half years of its initial 15-year, record-breaking run. (For seven years in the 1980s, ACL was the longest-running show in Broadway history; it has since been eclipsed by Cats, and later, The Phantom of the Opera.) And for the first while, he loved the association.

“There was a time it was great, when we never paid a cab fare. It was so huge. We were on coffee cups and beach towels at Bloomingdale’s. The difference it made to that city — it became the basis for the ‘I Love New York’ [tourism campaign]. It changed the trajectory of Broadway musicals.”

Then it got burdensome. There was the backlash that often accompanies unbridled success. “We were being picked apart everywhere.” The originals were trotted out for every major milestone: Longest run, historic closing, revivals and, of course, the Hamilton experience. Certain resentment lingered.

But he has, as he’s gotten older — he’s now 70 — realized profoundly how the experience changed not just his life, but countless lives across nearly half a century. And he chokes back emotions talking about it. He still gets emails from people the world over who find him on the internet, asking about his character; Jonathan Groff is a huge fan. And in many ways, ACL’s legacy will be to inspire the possible in the art form itself.

“As I got older, I realized the intense sense of responsibility. It’s why I teach now — to preserve the craft. We are at a crossroads in history,” Serrecchia says about the impact of coronavirus on live theater, which has shuttered Broadway until at least early 2021. “It only means Broadway will reinvent itself and be bigger and stronger. It always has. It’s really hard teaching singing and dancing and acting over Zoom. But I tell my students that their passion is what will contribute to the universe. We will take musical theater forward.”

And the next generation of gypsies will once again prove the impact in what they did for love.

Michael Serrechia-Robinson is a national treasure.

Fantastic!!!

Looooved Chorus line, what I did for love was my party piece for years. Saw it three times on Broadway. I’m almost 75 now, but this piece brought back awesome memories. I hope they revive it someday for future generations to see, I know my granddaughter would LOVE it. Thanks for the great memories ❤️💐❤️

Thanks for this celebration of Michael’s creative work! And he’s still rockin’ the stage!

Michael is truly a treasure. I have been greatly privileged to work with him and I hold that first experience in “A Class Act” dearly as one of my favorite shows. Thanks for this article and for sharing your life with the Dallas theatre community.