Rupert Everett not only stars as the fading dandy Oscar Wilde in ‘The Happy Prince,’ he wrote it and makes his directorial debut … all the great success.

At a crisis point in his career, out star Rupert Everett decided to make his own luck by writing, directing and starring in the life of Oscar Wilde

At the height of Rupert Everett’s stardom, he was costarring alongside Julia Roberts in My Best Friend’s Wedding and opposite one of his best friends, Madonna, in The Next Best Thing and voicing the character of Prince Charming in the Shrek movies. But the most interesting thing on Everett’s resume is not a movie role, rather for what he did in 1989, which was unprecedented then: he was one of the first major actors to come out of the closet.

And if he had to do it all over again, would he have done it when he did?

“Yes, because I loved going to clubs and discos and stuff like that. And there was never that question for me to lead that kind of closeted gay life that might be quite fun, you know, where you’re just in your own space, and you order in, or whatever it is,” Everett says, breaking out into a mischievous laugh. “I loved the whole gay culture. So, for me, to even consider anything other than being out wasn’t an option. Also, if you’re going to lie about yourself, it’s a tough thing. It’s a negation of yourself.”

We’re chatting this day because Everett is promoting his latest film, The Happy Prince — a movie based on the later years of Oscar Wilde’s life, which Everett wrote, directed and stars in. Why the fascination with the Victorian bon vivant?

“My fascination with Oscar Wilde began when I was 6 years old and my mother read me The Happy Prince at night in bed,” he recalls. “I remember it very well. I was enraptured by the story and inconsolable at the end. Coming from a military family with a distinctly pre-Freudian worldview … it was probably the first time I heard about love and suffering and that there was a terrible price to be paid for it. The Happy Prince was a turning point.”

Everett moved to London in 1975, and as difficult as it is to imagine now, gay sex had only been legal for seven years. “The police — making the most of the ambiguity in the 1967 law — continued to raid and arrest people for homosexual acts in public and so there was a palpable feeling that we were stepping in Oscar’s freshly trodden footprints on those unlucky occasions when we were herded into paddy wagons and taken down to the police station for the night,” Everett says. The knowledge even informed his career choices.

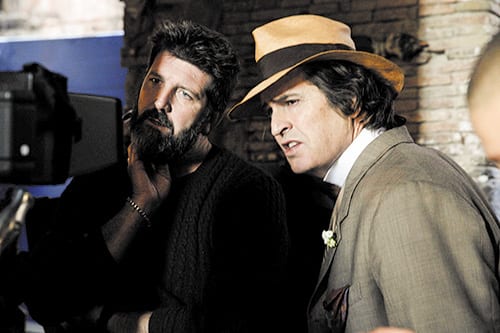

Everett directs himself in ‘Happy Prince’

“Later I became an actor and performed in The Picture of Dorian Gray. It was a great success. When an actor discovers a writer who really works for him — that he can perform well and make his own — it is the beginning of a treasured relationship,” he says. “Something between me and the text sparked. A few years later I performed The Importance of Being Earnest [in French] at the Theatre National de Chaillot in Paris and then made two films from Wilde plays: An Ideal Husband and The Importance of Being Earnest.”

It was around that time that his career “dried up — literally evaporated overnight,” he says. And so Everett realized he needed to make him own opportunities.

“I began to write; I decided to create a role for myself. If no one else would employ me I would employ myself,” he says. “Oscar Wilde seemed to be the ideal character — not the Wilde of folklore, the iconic family man, the life and soul of the café royal, but a different Wilde — the fallen star, the last great vagabond of the 19th century, punished and crushed by society, yet somehow surviving. I would write the Passion of Wilde!”

Writing it was one thing; getting it made was another.

“After I had been turned down by almost every director of note, I decided to make the film myself,” Everett says. “If I had been in possession of a crystal ball I would not have embarked on such a journey. It took 10 years to get to preproduction.

“I didn’t think of immersing myself fully in the beginning, because I never wanted to be the director,” he continues. “I had written a couple of books [about Oscar Wilde, in 2000 and 2005], and I really wanted to write a script in which I could act and maybe resuscitate my career to a certain extent. So, Oscar Wilde seemed to be the perfect character in that he’s a great inspiration to me — the patron saint figure in a way. After sending the screenplay to a number of directors and seeing them all pass on the project, I realized if a screenplay is not directed it is nothing. You can’t publish it in a magazine. It’s nothing. And I thought, I’m going to do it myself. And that’s what happened.”

The version of Oscar Wilde’s life that Everett tells is both depressing and sad, as it focuses on the final years of his life, following his late-release from jail, after having been sent there for engaging in sodomy. Much of the film features Wilde on his deathbed, recalling the horrible atrocities that befell him.

“I focused on the latter part of Wilde’s life partly because the other three films about him focus on the successful part of his life, and I think that is a little bit of an easy get out for people to just look at the good part,” Everett says. “What society did to him was this: They put him in prison, and then they imprisoned him in liberty, and it happened just for the fact of being a homosexual man. So, for me, as a homosexual man, this is the important part of the story. It’s like the Passion of Oscar, like Christians have The Passion of Christ. And seeing Wilde go from one stage to another is a great inspiration. And I think he was also amazing in his exile. He was never a victim.”

Having made his directorial debut, albeit with reservations, would he direct another film?

“I would,” he says. “It’s kind of like childbirth when you’re directing a movie. You think when you’re in labor, ‘Oh, god, I’m never doing this again.’ But as soon as the baby is out of the bag, you think, I can’t remember all that pain. I’m now bristling with new ideas.”

At 59, this summer Everett moved back to England to help take care of his elderly mother.

“It’s is like going back in the closet!” he says with a chuckle. “You go immediately back to the relationship you had when you were 14, and my mum doesn’t realize that I’m 59, and she kind of orders me around. I have to close windows, open bottles and do everything. That is quite difficult. But it’s nice.”

— Tim Nasson